Progress and growth as humans necessitates change, whether at the social, organizational, or individual level. And change is hard, very hard! You and I know this to be true because of our shared human experience. Some changes are much harder than others, even if we strongly believe in and desire the outcomes of the change. This year has many of us reflecting on ways we would like to change, myself included. The desire to change is not enough. Change is not a function of sheer will power. New Year’s resolutions often are maligned as ineffective–gyms and fitness centers usually are extra crowded in January with people who genuinely want to be healthier yet by March the attendance numbers have thinned to primarily just the regulars. Why aren’t the desire and good intentions to change sufficient?

Humans have a built in change resistance. We are highly adept at it. We construct systems, both conscious–policies, procedures, laws, roles and responsibilities, organizational charts, etc.–and unconscious–habits, implicit associations, mental models, team dynamics, informal ways to get things done in organizations, etc.–in service of this. There is a benefit to this. Predictability. Order. Efficient and effective interactions with others. There is a cost to this though; we sabotage our desired change efforts. Robert Kegan and Lisa Laskow Lahey, psychologists and organizational development researchers and practitioners out of the Harvard School of Education, have coined this as our immunity to change. (Mentioned in my previous blog post Resilience: When staring in the face of fear.) We have an immune system that attacks change because often change is bad, except when it is not. Our immune system doesn’t know the difference though.

At the social, organizational, and individual level, our systems are perfectly designed to produce the results we are getting. In order for us to change, we need to change the system. To change the system we must first understand the system. We need to examine it, identifying our mindsets and behaviors, digging into where they came from, and testing their implicit assumptions. Over time, this allows us to overcome our internal change resistance, shifting our mindset and behaviors. The result: You and your system changes.

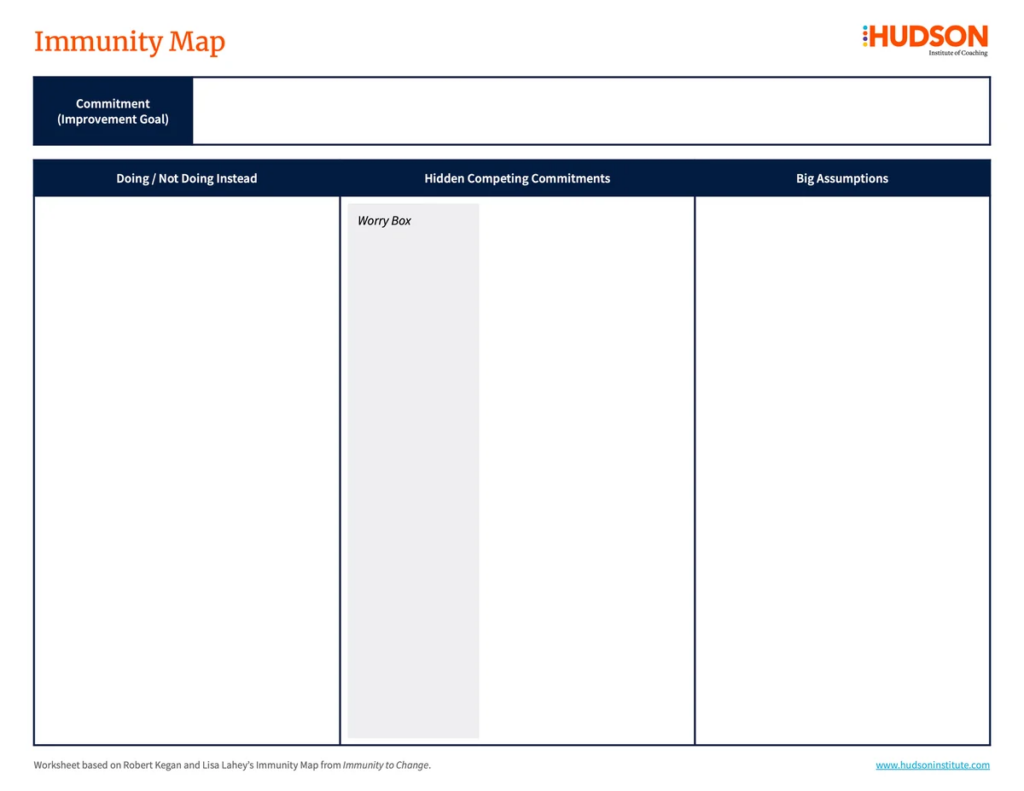

Immunity map

In service of this, Kegan and Lahey have created an immunity map, which I have found to be one of the most approachable and powerful frameworks to diagnose and shift my behaviors that get in the way of me changing. To demonstrate how to use the tool, we will walk through the creation of one of my actual immunity maps–this was a real exercise for me, not a hypothetical one. The steps to create an immunity map are as follows:

- Define your improvement goal.

- Conduct a fearless inventory of what you are doing or not doing instead.

- Unearth your hidden competing commitments to your improvement goal.

- Identify your big assumptions that breathe life into your hidden competing commitments.

- Assess your immunity map. (Likely you will need to go deeper than where you ended up on your first attempt, repeating steps 1 through 4.)

- Tackle your big assumptions by running tests.

I strongly suggest you create your own immunity map as you read along so this is a practical exercise for you, rather than a theoretical experience.

Before we explain the first step, download our version of the immunity map template.

Defining Your Improvement Goal

Your improvement goal is the behavior you are committed to improving. It is the thing you are working on.

An improvement goal is:

- Specific! Improvement goals need focus and clear parameters.

- Important to you. This is your commitment, not someone else’s. It needs to matter to you. If you don’t have the ability and desire to work on it or this exercise will be moot.

- Good improvement goals are formed with input from others, such as bosses, peers, direct reports, stakeholders, and friends and family.

- Framed positively–what you want to be or become–versus what you want to stop being or doing. I want to enjoy an active lifestyle versus I don’t want to be overweight.

- It includes why this is important–this will make it more real and motivating for you.

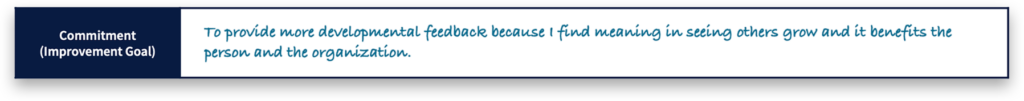

What I wrote: To provide more developmental feedback because I find meaning in seeing others grow and it benefits the person and the organization.

How I identified my answer: In 2011 I took a workshop called Crucial Conversations, which is about having difficult conversations well and with heart. This was the impetus for me pivoting from a career in accounting to leadership development. In the previous organization in which I worked, we had ample data confirming managers were not having enough feedback conversations, despite their team members wanting them in service of their growth and development. Even though I believed deeply in the power of feedback and had been trained regularly on how to share it, I still was not having enough feedback conversations.

Your turn: Now it is your turn to identify your improvement goal. Getting this step right is imperative in order to successfully overcome your immunity to change. The more specific, the better.

If you find yourself staring at the blank first column in your immunity map, ask yourself the following questions.

- What is the one thing that is holding me back the most?

- What is the most highly leveraged thing I could change?

- What is my heart telling me to do but my brain and behavior aren’t letting me?

An improvement goal lies somewhere in your answers.

Once you’ve narrowed it down to a specific goal, it’s time to assess and refine. Are you truly committed to it? Does it matter to you?

Think about why this is important:

- How will it benefit you?

- How will you grow as a person?

- How will it impact others around you, i.e., your loved ones and those you lead?

- What will be the benefit to your family, team, and organization?

- What will be the cost of not making this change?

Remember that input from a few people who know you well, at work and at home, will help you refine your improvement goal. Ask them if they think your improvement goal is specific enough and if it matters. Their responses will help you refine your improvement goal. It also sends a signal that you are going to be changing and will help them support, versus shut down, your change efforts–remember they too have a change resistance. Friends and family are especially helpful resources. Often colleagues sugar coat their input on our improvement goals; whereas, loved ones tend to say it as it is with words like, “Yes, that is something you can work on. Although, if you really want to work on it, then you should…”

Refine and adjust based on their feedback.

Conducting a Fearless Inventory

Column 2 is where we conduct a fearless inventory of all the things you are doing, or not doing, that are not supporting, getting in the way of, or even sabotaging your improvement goal.

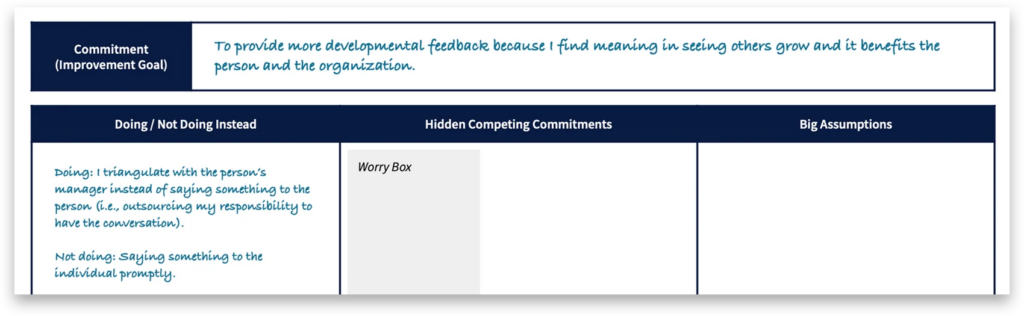

What I wrote:

- Doing: I triangulate with the person’s manager instead of saying something to the person (i.e., outsourcing my responsibility to have the conversation).

- Not doing: Say something to the individual promptly.

How I identified my answers: Remember, my improvement goal is to provide more developmental feedback because I find meaning in seeing others grow and it benefits the person and the organization. Even though I was not having enough feedback conversations, I knew I had not abandoned my commitment. So I thought about clever workarounds I was using–was I deceiving myself into believing I was achieving my goal some other way? Was I doing the opposite of my goal? Yes, I had a habit of having the right conversation with the wrong person. At first, I did not want to admit this; I wanted to justify my approach as a more thoughtful and relationship-oriented way to honor my commitment. When I looked at the behavior more closely and at the results, this simply did not pass the sniff test–I had to call BS on myself.

Your turn: Conduct your own fearless inventory to populate the second column of your immunity map with what you are doing that doesn’t support your improvement goal and not doing that would support it. A few tips to keep in mind:

- The more specific, the better.

- List behaviors, not beliefs.

- Go for volume and honesty.

- Don’t write things that are working on behalf of your improvement goal.

- Resist the temptation to analyze why you are doing (or not doing) these behaviors. There is no need to come up with a plan to change your behaviors in this step. That comes later. It’s a deeper work. As explained in Resilience: When staring in the face of fear, any solutions you come up with now likely will be technical solutions to an adaptive challenge. Remember technical solutions have right and wrong answers; whereas, adaptive challenges entail remapping mental models, shifting mindsets, forming new habits, and creating new ways of being. If a technical solution were sufficient to achieve your improvement goal, you would be doing it already.

Unearthing Your Hidden Competing Commitments

A hidden competing commitment is a behavior or mindset we unconsciously follow that conflicts with our improvement goal. It is something we hold dear that we implicitly assume we would lose if we were to fully lean into our improvement goal. Our improvement goal and hidden competing commitment seem to be mutually exclusive–we will find later they likely are not.

What I wrote:

- To honor other’s personal space and business

- To be liked

- To honor the way I was raised: “If you have nothing nice to say, don’t say anything at all.”

- To avoid conflict, avoid strife, and create harmony. (Don’t recreate the “broken” environment in which I grew up.)

- To feel in control and competent.

How I identified my answers: Before jumping to identify my hidden competing commitments, I first numbed my change resistance. Otherwise, there is no way I would have let myself get anywhere close to those raw, exposed nerve endings. First, I filled out the worry box at the top of column 3 in the immunity map. I asked myself what my deepest worries were about the behavior I was looking to change. What is the worst thing that could happen if I were to give someone feedback? Why did I find myself wanting to avoid it? The experience was cathartic and began to make it feel safe to identify my hidden competing commitments. The worries were actually excuses supporting my hidden competing commitments:

- What if I’m wrong?

- What if I ruin the relationship?

- What if I “damage” the person?

- What if I trigger the person and they get “reactive?”

- What if they end up not liking me?

- What if they don’t change? Will I have to take a drastic action I would prefer avoiding?

After completing my list of worries, I realized every one of my worries is directly tied to a learned behavior meant to protect myself from what made me feel unsafe in my family and community growing up. This began to unlock my ability to identify my hidden competing commitments.

Your turn: This step might sound scary. Our hidden competing commitments are hidden for a reason–at the unconscious level we do not want to acknowledge how we are sabotaging the things we say are important to us. Self-sabotage might sound irrational. It isn’t! We have worries. Our hidden competing commitments are defense mechanisms to protect us in case these worries come true. This is your immunity to change–white blood cells attacking an invader. It is a healthy mechanism, but not a helpful one if it gets in the way of your improvement goal. (If we stretch this analogy further, we know this mechanism can cease being healthy.)

If you act on your improvement goal, what are you afraid might happen? What might you lose? These are your worries. What if I’m wrong?

Why are you afraid of these happenings or this loss? People will see me as incompetent and unable to control a situation as a leader.

Underneath this answer is a need, a hidden competing commitment. I have a hidden competing commitment to feel in control and competent. (Why? It was a learned behavior, a defense mechanism, that kept me safe amidst the trauma of my childhood–control helped me avoid the chaos and turmoil, competence and intellect were recognized and rewarded.)

After you get your worries out and have refined them, generate possible hidden competing commitments. Give yourself the grace to spend some time with this. Assume you haven’t gone deep enough identifying your hidden competing commitments on your first pass.

This step is important. Remember the system is perfectly designed to get the results you are getting. As Kegan and Lahey describe it, we have one foot on the brake even as we have one foot on the gas pedal. We are exposing our change resistance, our immunity to change. This immunity was helpful at one point in our lives. Yet, it has served its purpose. Its utility has ended.

If we don’t adequately identify our hidden competing commitments, we won’t be able to overcome our immunity to change. Instead the system of change resistance will perpetuate its self-reinforcement.

You don’t need to take any action with this column. Just get it all out on paper.

Identifying Your Big Assumptions

Big assumptions are assumptions we are making that breathe life into our hidden competing commitments. They are the assumed mutual exclusion between our improvement goal and our hidden competing commitment. They are the thing that needs to be true in order for our hidden competing commitment to not be met if we lean into our improvement goal. They are big in their breadth, depth, and foundational nature.

What I wrote:

- My words are more powerful than the individual’s resourcefulness and lifetime of experience. (In other words, I could unintentionally cause irreversible damage to the person.)

- Feedback = conflict.

- Conflict and strife are bad. Harmony is good.

- Feedback and being liked are mutually exclusive.

- The things I was taught in my childhood were right.

- Life is black and white (versus gray, gray, gray).

- I won’t know how to respond when someone “reacts.”

- Relationships are fragile.

- People don’t really want feedback. And they rarely change.

- Others won’t listen to feedback. They don’t want to hear it. And they definitely don’t want to hear it from me.

- By giving feedback, I will recreate the family dysfunction I experienced growing up.

How I identified my answers: After identifying my hidden competing commitments, I tried to step out of my mental model about giving feedback and examine it as an objective observer. I asked myself what needed to be true about giving feedback in order for my worries to come true and my hidden competing commitments to not be met. What assumptions was I unconsciously making? I had to give this time, to sit with it for a while, as I unearthed deeper and more meaningful awareness of assumptions I had been making my entire adult life.

One of my worries was: What if I trigger the person and they get “reactive?”

This led to identifying a hidden competing commitment: To avoid conflict, avoid strife, and create harmony. (Don’t recreate the “broken” environment in which I grew up.)

I saw lots of histrionic behavior growing up–screaming, marathon yelling matches, weaponizing threats about self-harm, etc. My mental model was this environment was “bad” and avoid recreating it at all costs. Beneath this mental model, I was making the following big assumptions:

- Feedback = conflict

- Conflict and strife are bad. Harmony is good.

- By giving feedback, I will recreate the family dysfunction I experienced growing up.

These assumptions had some accuracy and usefulness when they were formed; however, my environment has long since changed. These assumptions felt like reality. Hard, carved in stone reality. Yet I realized they were BIG assumptions to be making. It was time to reassess their validity.

Your turn: In column 4 of your immunity map, capture your big assumptions. In order for your worries to be valid, what assumptions are you making?

Take your time making this list. Revisit it, ask yourself provocative, probing questions, such as:

- How do I explain this to myself?

- Beneath this assumption, what assumption am I making?

- What assumption am I embarrassed, ashamed, or afraid to admit I am making?

- If I were to give myself the freedom to rewrite my life narrative, how would I describe this?

- What am I pretending to know to be true?

If you are adequately capturing your big assumptions, you’ll get this on the head and heart level. There should be a feeling when you read what you wrote. (And you’ll get why a technical approach won’t work–these run deep to the core of who you are.)

We cannot change unless we deal with these big assumptions. Otherwise we will be taking a technical approach to an adaptive challenge. The “white knuckled” approach of gripping on for dear life, willing yourself to change only gets you so far. At some point, resolve fails as our immunity to change generates antibodies that attack and kill our good intentions.

Assessing Your Immunity Map

Next we will assess our immunity map and then look for where the blind spot is in the big assumptions. What is the error in it? We’ll exploit that in order to change.

Before we proceed, check your immunity map for common pitfalls:

- Not being specific enough with your improvement goal.

- Having someone else’s commitment. It has to be important to you, or else you won’t work on this.

- Not having control over or the ability to influence our improvement goal.

- Not getting input from others on your improvement goal, especially loved ones.

- Not going deep enough surfacing your hidden competing commitments and big assumptions.

Remember it is not sufficient to “white knuckle” yourself to change via sheer will as you read your hidden commitments. You must shift your relationship with your big assumptions! You will achieve this through a combination of mindset and behavioral shifts.

Running Tests to Tackle Your Big Assumptions

Run tests against big assumptions by doing the following:

- Define the test

- Define how you will know the test is successful in the short-term

- Define what long-term success looks like

- Refine your commitment and make your immunity map more specific

- Repeat

Define the test

Tests don’t have to be actions–at least not right away. For example, if I am testing my big assumption Feedback = conflict, I could identify someone who is particularly skillful at giving feedback. Then observe them providing feedback several times. Sounds like a safe test, right?

Then you can graduate by testing with actions. I could ask the skillful feedback provider for pointers, gradually move to sharing light observations with others as a form of providing feedback, and finally graduating to testing having actual feedback conversations.

Define short-term success

Carrying the above example forward, maybe short-term success is I notice my resistance to providing feedback.

Define long-term success

Long-term success could be I share feedback as second nature. In other words, it has become a way of being so much so it doesn’t feel like feedback to me or the other person. The nerves are gone and it feels like I am merely offering an observation paired with a coaching question, “I noticed when you did xyz it had the impact of abc. What do you make of that?”

Notice how much more effective this approach is. Instead of willing myself to have more feedback conversations, I have diagnosed what my hidden competing commitments are, why they exist, and invalidated their underlying assumptions. I have shifted from setting myself up to occasionally have nerve-wracking feedback conversations whenever I find the gumption–a blunt instrument–to comfortably having regular, real-time, skillful coaching conversations.

How Did I Do?

Has it worked? In the last three months I have given in-person feedback to 75% of my coworkers. Not all of the conversations were as skillful as I would have liked. (And a few times I avoided having what should have been “the first” conversation.) Yet, our team has never been stronger, more collaborative, or more productive. Multiple people have thanked me for the feedback, noting how it helped them grow, engendered trust, and increased their respect for my leadership. None of the conversations have validated my big assumptions; in fact, they have done the opposite. So yes, it is working, and I am still on the developmental journey.

Wait, was this a post on how to give effective feedback?

Conclusion

We all have an immunity to change. It is useful, helpful, and healthy, except when we want to improve ourselves as individuals and leaders. That’s when it’s more like an autoimmune condition. Our systems attack the behaviors that support our change effort instead of the big assumptions that keep us stuck in our old patterns. The process of filling out your immunity map is an extremely effective way to redirect those antibodies against your unconscious resistance to change. Build the map, then test those assumptions until they change.

References:

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (2009). Immunity to Change: How to Overcome It and Unlock the Potential in Yourself. Harvard UP.

Heifetz, R., Linsky, M., & Grashow, A. (2009). The Practice of Adaptive Leadership: Tools and Tactics for Changing Your Organization and the World. Harvard Business Review Press.

Kegan, R., & Lahey, L. L. (November 2001). The real reason people won’t change, Harvard Business Review.

![[Video] Podcast Rewatch: The Midlife Chrysalis Podcast](https://hudsoninstitute.com/wp-content/uploads/2026/02/Insight-blog-video-thumbnail.png)